19 Jan India goes big to woo investors at World Economic Forum

India’s position on the global value chain is shifting due to government incentives and a digitally savvy economy

Getty Premiums

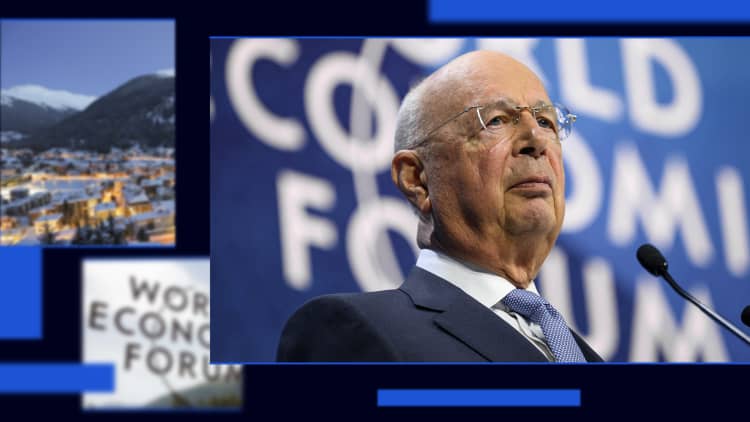

DAVOS, Switzerland — Along the Davos Promenade, attendees of the World Economic Forum stumble across the WeLead Lounge, a repurposed storefront showcasing India’s female leadership and talent. There’s also the India Engagement Center, a space promoting India’s growth story, digital infrastructure, and its burgeoning startup ecosystem.

Elsewhere at the forum, Indian technology and consulting giants Wipro, Infosys, Tata and HCLTech are out in full force to showcase the country’s prowess in key technologies like artificial intelligence, the subject that’s on everyone’s lips.

The hefty Davos promotions come after India surpassed China last year as the world’s biggest country by population. Now India is touting its growing strength as a nation of innovation and as a global business hub in front of some of the world’s richest and most powerful people.

“India’s presence is certainly sizable — it has some of the most sought-after spots on the main promenade for tech companies,” Ravi Agrawal, editor-in-chief of Foreign Policy and former CNN India bureau chief, told CNBC at Davos. “As China’s economy slows down, India’s relatively rapid growth stands out as a clear opportunity for investors in Davos looking for bright spots.”

China’s gross domestic product increased 5.2% last year, up from 3% in 2022 but down from 8.1% the year prior. India grew 7.2% in the last fiscal year, down from just over 9% a year earlier.

India has been increasingly looking to promote itself as a more dominant figure on the world stage when it comes to technology and business. States such as Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Karnataka have their own presence at Davos, positioning themselves as tech hubs for manufacturing and AI.

“In that sense, the separate state pavilions send a message — that various regions in India are competing with each other to offer global companies the best access,” said Agrawal, who has been attending Davos for more than a decade and is the author of “India Connected,” which chronicles how the smartphone led to a more connected and democratic India.

India still faces plenty of challenges.

In most years, India sees more people migrate out of the country than into it, according to date from the World Bank. In 2021, net migration topped 300,000. The rupee, meanwhile, has weakened heavily versus the dollar, pressured by high U.S. interest rates and volatile oil prices.

One of the key risks of doing business in India, according to the International Trade Administration, is “price sensitivity” among consumers and businesses.

“The challenge, as always, is whether India can actually make it easier to do business there, and whether India’s domestic consumers can spend enough to make continued global investment worth it,” Agrawal said.

Seeking foreign investment

Still, foreign direct investment has surged in the last few years, increasing from $36 billion in 2014, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was first elected to office, to $70.9 billion in 2023, according to figures compiled by digital media publisher Visual Capitalist, which used Reserve Bank of India and S&P Global data.

Dell, HP, Lenovo and other major manufacturers are committing to making their products locally in India as part of the country’s production-linked incentive scheme.

Apple is one of the biggest examples of a U.S. company that’s looked to divert its production from China and source manufacturing from India to avoid facing supply issues with the iPhone and other key products.

Last year, Apple opened its first store in India, highlighting the importance of the market to the iPhone maker’s future. The store, called Apple BKC, is in the populous city of Mumbai.

“We had an all-time revenue record in India,” Apple CEO Tim Cook said on the company’s latest earnings call in November, in response to an analyst’s question about the company’s momentum there. “It’s an incredibly exciting market for us and a major focus of ours. We have a low share in a large market. And so it would seem that there’s a lot of headroom.”

Chief Executive Officer of Apple Tim Cook gestures during the opening of Apple’s first retail store in India, in Mumbai on April 18, 2023.

Punit Paranjpe | AFP | Getty Images

India is also making a big push to encourage investment from U.S. chipmakers. The country hosted a major semiconductor industry event last year, SemiconIndia, with chip producers from the U.S. invited to tout their investments in India and announce new ones.

AMD, which is chasing Nvidia in the AI chip market, said it plans to invest around $400 million in India over the next five years, including a new campus in Bangalore that will be the company’s largest design center. And Micron announced plans to invest up to $825 million toward setting up a semiconductor assembly and testing facility in the state of Gujarat.

Jack Hidary, CEO of SandboxAQ, which applies AI and quantum computing tech to areas like cybersecurity and drug discovery, said India is seeing accelerating adoption of technology due to inefficiencies in health care and other core public services.

AI, in particular, offers an opportunity for India to stand out from the pack, Hidary said.

“This is a transformation that is well beyond even the mobile phone,” Hidary said. After the U.S. and China started investing in mobile infrastructure two decades ago, “almost everyone in those countries quickly got a smartphone and had access to the web and to apps,” he said.

However, “600 million people in India out of the 1.3 billion still don’t have a smartphone,” he said, adding “that’s about to change.”

Hidary said Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s smartphone company Jio will serve about 600 million people in India through a $12 device. Ambani, Asia’s richest person, is also in Davos for WEF.

“He and a few other services in India are going to close that digital gap literally in the next three years,” Hidary said. Broadly, India is making a big push at the event because its leaders “know it’s a moment of great transformation,” Hidary said.

Big year for India

It’s poised to be a pivotal year for India in other ways. General elections are set to be held between April and May, as Modi seeks reelection.

During Modi’s tenure, major U.S. tech companies, including Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon have made massive bets on India. Amazon invested $2 billion into the country in 2014, and another $3 billion in 2016. Walmart acquired e-commerce company Flipkart for $16 billion in 2018.

In 2020, Meta invested $5.7 billion in Jio, the digital arm of Ambani’s Reliance Industries. Google followed up by pouring $4.5 billion into the company.

As India has ascended, China has faced mounting trouble on the world stage, with the U.S. leading a charge to isolate the world’s second-largest economy particularly when it comes to accessing key technology.

Beijing has for months been unable to import some of the most advanced chips from U.S. companies such as Nvidia, Intel, and AMD.

Ian Bremmer, president and founder of Eurasia Group, told CNBC that India has a good chance to strengthen further due in large part to being a democracy.

“The good thing about India is the fact that it’s a stable country, with a very popular leader,” Bremmer said. “They’re about to have an election that’s going to be absolutely uncontroversial, and free and fair. And their growth is pretty strong.”

Bremmer contrasted India with the U.S., noting that it’s a “very decentralized country,” with lots of states almost competing against each other for investment. He said he could imagine U.S. states eventually taking a similar approach.

“It’s not inconceivable to me that in five years time at Davos, you would see individual U.S. states deciding to do the same thing,” he said. “Texas would be mopping up on fossil fuels and sustainable energy, if they had a storefront in Davos this year. And you know, California, frankly, would, too.”

— CNBC’s Arjun Kharpal contributed to this report

WATCH: CNBC’s full interview with Deutsche Bank CEO Christian Sewing