10 Mar China’s ‘two sessions’ 2024: new mandate, party control push central bank beyond ordinary role

Rather than take drastic action to silo China from the US and insulate its economy from what already looked like a ticking time bomb, Wang promised his old friend the country would not dump its massive holdings of US treasury bills.

Though that news was a massive relief for the imperiled US economy, it did not come lightly. According to Paulson’s memoir, published in 2010, Wang ended the call with a warning: “I know you think this may end all of your problems, but it may not be over yet.”

If anything, that was an understatement. The earth-shattering event that followed – brought on by deregulation, speculation, over-leveraging and a reckless intrusion of Wall Street into housing markets – triggered a widespread reconsideration of the Western model by economists and cadres in China’s financial sector.

That decisive moment, and the years of tensions and trade war that would follow, hardened Beijing’s determination to walk a different road.

The amendment is expected to be approved by lawmakers at this year’s session of the top legislature, which will end on Monday.

In China’s context, the party is always in charge of all major matters

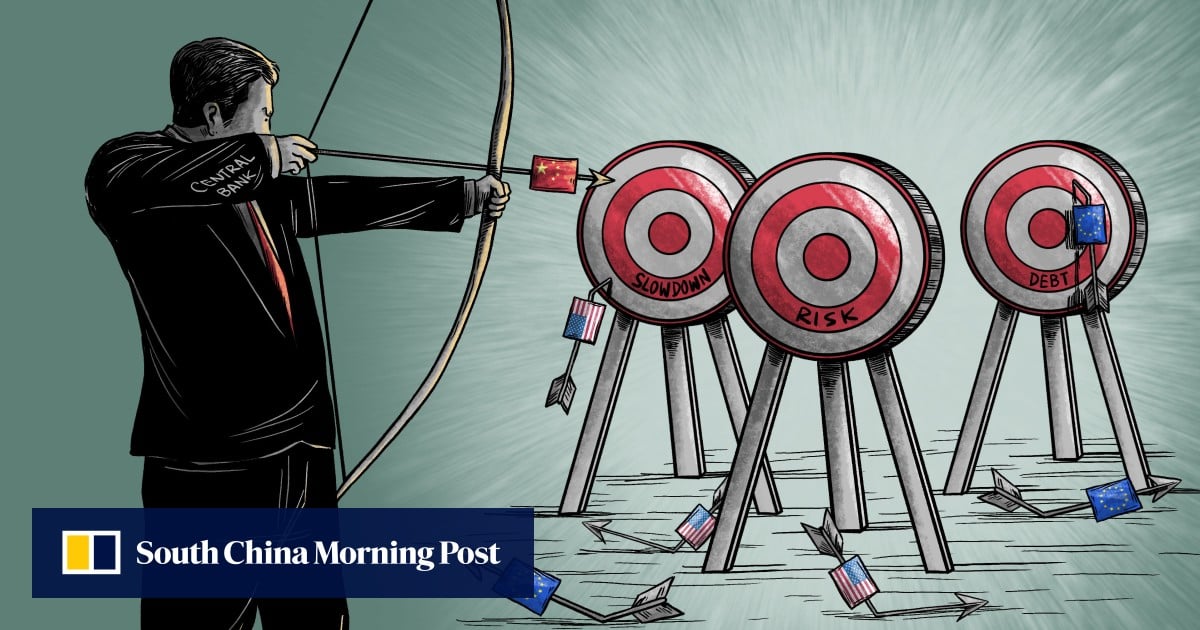

For many observers, the PBOC has already departed from its ostensible mission to become a Western-style central bank. Those institutions, like the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, carry relative independence in policymaking and hold inflation control as their primary responsibility.

Instead, two laws in the drafting process appear poised to more explicitly define the bank’s role as a powerful engine for Beijing’s economic prosperity – particularly its real economy, or non-financial sectors, which are proportionally far greater than those of the US.

“In China’s context, the party is always in charge of all major matters,” said Rui Meng, a professor of finance at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai.

Preventing, resolving China’s financial risks are ‘eternal theme’: Xi Jinping

Preventing, resolving China’s financial risks are ‘eternal theme’: Xi Jinping

“A smaller, more streamlined but powerful central bank is a key pillar of the ambitions [to be a] financial superpower.”

However, as Xi enumerated in a speech at the Central Party School in January, success for the country’s broad financial aspirations will rest on several factors, a strong central bank among them.

With the volume of change already undertaken and in the works, Rui said, the question of whether the PBOC resembles its Western peers is no longer relevant.

“It has been assigned important tasks,” he said. “The new central bank has become focused on fewer tasks, but they are more vital, and ones Western central banks [seldom do]: serving the economy and fighting risk.”

The new mandate comes after years of deep analysis of the Western financial system, changes in domestic circumstances and rising geopolitical tensions.

It has also watched with great interest the situation in Russia, where blanket financial sanctions – including the freezing of central bank assets and its removal from international financial messaging service Swift – have been imposed after the Ukraine war began in February 2022.

Consequently, China has stepped up its criticism of US hegemony and weaponisation of the dollar while prioritising risk prevention and control in its financial work, which includes precautionary measures and counteroffensives against sanctions regimes both real and hypothetical.

A superpower like China has to make precautions and contingency planning for a full-blown financial war

Analysts have expected greater functionality for the Chinese central bank in defending financial security, as well, as it has an irreplaceable role in handling several issues of concern: internationalisation of the yuan; establishing a digital currency; backing the country’s global infrastructure strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative; managing capital flows and countering sanctions in the event of a financial decoupling.

“Beijing has prioritised financial security and control against this international and geopolitical backdrop. The PBOC plays a central role here,” said Yan Shaohua, a researcher with Fudan University’s Institute of International Studies.

“A superpower like China has to make precautions and contingency planning for a full-blown financial war, even though it’s unlikely – at least for now.”

Beijing’s yuan internationalisation plan, which promotes greater use of the Chinese currency in overseas payments, trade settlements, forex trading and government reserves, dates back to 2009, when former PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan approved its use for trade settlements on a limited basis.

Zhou spearheaded reform of Beijing’s financial system to bring the bank’s work closer to international norms in his early years at the helm, instituting a managed float regime for the yuan’s exchange rate in July 2005, as well as liberalisation of current accounts and the recruitment of overseas Chinese talent to restructure operations.

After the global financial crisis, he spent time and political capital on improving mechanisms to rebalance the prominence of the US dollar, convincing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2015 to add the yuan to the basket of currencies designated for special drawing rights, and was a pioneer among major economies in implementing a central bank digital currency, the e-CNY.

These moves come in the context of broad directives from Xi, who has requested greater balance between financial security and opening up and called for an independent, secure and efficient financial infrastructure.

More foreign investors to get a crack at China’s repo market in latest tweak

More foreign investors to get a crack at China’s repo market in latest tweak

Russia, Brazil and several other countries have been using the yuan more frequently. But the Chinese currency’s place in international trades remains far behind the US dollar.

The yuan’s share of cross-border purchases was 4.5 per cent in January, compared to 46.6 per cent for the US dollar according to Swift data – nearly double the figure from the previous year, but starting from a low baseline. Government foreign reserves held in yuan stood at 2.4 per cent of the total for the third quarter of 2023 according to the IMF, much lower than the US dollar’s 59.2 per cent.

To hasten the shedding of China’s reliance on Western financial infrastructure, authorities have also built the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System to make international yuan settlements easier. Thousands of financial institutions have signed on, and in 2022, 4.4 million transactions were handled by the system, processing a total of 96.7 trillion yuan (US$13.4 trillion) through its facility.

The central bank is also expected to be more aggressive in fighting for China’s say in international affairs by firming up ties through the Belt and Road Initiative and the Brics bloc of emerging economies, as well as winning a more prominent spot in international organizations led by Western countries.

Lu Lei, deputy governor of the PBOC, discussed China’s position in “improving the international financial framework” at the G20 meeting of finance ministers and central bank governors in late February in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The country has long demanded a higher voting share at the Washington-based IMF, contending the proportionality of its 6 per cent compared to the US’ 16.5 per cent in proposed reforms for the United Nations agency.

Were all these plans and initiatives to come to fruition, it would alter the domestic financial landscape in numerous ways. The size of the monetary supply pumped into the economy, cost of funds, direction of capital flows, international monetary cooperation would all irrevocably change, analysts said, as would the ways Wall Street banks and their Chinese peers do business in the world’s second-largest financial market – one with 452 trillion yuan in assets per PBOC figures.

During Yi’s tenure as central bank governor between 2018 and 2023, the PBOC has diverged from the policy approaches of the Federal Reserve, as the two countries are officially in different economic cycles.

Despite this, he resisted calls for debt monetisation and refrained from a massive stimulus, as the bank was preoccupied with the debt load that came from previous rounds of spending to offset market slowdowns and spur growth.

Instead, Yi, who earned a doctorate in economics in the US and worked as an associate professor there in the late 1980s and early 1990s, created structural tools to support the private economy, small businesses, tech and other areas spotlighted by the central government.

Now, under Pan, analysts anticipate a stronger pro-growth stance. The bank’s leadership and decision-making structures are more formally bound to the Communist Party, and the world’s second-largest economy is fighting a war of narratives to play up its prospects.

The central bank convened a meeting of regulatory officials and representatives from major banks in late February, rallying funding for five areas deemed a priority by Xi: science and technology, the green economy, inclusive finance, care for the elderly and the digital economy.

Monetary authorities have also taken a firmer hand to boost growth directly . New loans in January hit 4.92 trillion yuan, a monthly record, adding to an already considerable balance of 22.75 trillion yuan for last year.

But in the present environment, China may be more reluctant to enhance capital account liberalisation or the free float of yuan exchange rates, measures long pushed by Western observers but viewed by Beijing’s policymakers as risky.

Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at French investment bank Natixis and a former adviser at the European Central Bank, downplayed the prospect of major liberalisation.

We’ll create a good monetary and financial environment

“We haven’t seen any additional reforms in terms of the way interest rates operate or capital controls,” she said.

At a press conference on Wednesday, held on the sidelines of the “two sessions” parliamentary meetings in Beijing, Pan announced the creation of two more relending tools for tech innovation and renovation, in line with the leadership’s call to fund the country’s upgrade to high-value industries and advanced manufacturing.

Pan said China has “ample monetary policy space” and a “deep toolbox” to accomplish its goals.

“We’ll create a good monetary and financial environment for the operation of financial markets and the economy,” he said on Wednesday.

‘A step in the right direction’: China makes largest cut to key mortgage rate

‘A step in the right direction’: China makes largest cut to key mortgage rate

Li Xunlei, chief economist at Zhongtai Securities, said special refinancing debts and the “three key projects” – affordable housing, renovations for urban villages and the construction of emergency public facilities – would need support from the Chinese central bank to bolster the money supply.

“Its balance sheet may expand further this year,” he wrote in a note last week.

The PBOC’s new role will be finalised with the passage of a law on financial stability and an amendment to the laws governing the bank.

According to a draft version of the revised PBOC law, the bank will legalise the digital yuan and spearhead the country’s financial security review process.

Jin Penghui, deputy director of the bank’s Shanghai headquarters, urged adoption of the amendment to reflect the PBOC’s changing responsibilities.

“The amendment should concentrate on the three tasks given to the PBOC: serving the real economy, controlling risks and deepening reforms, with a focus on building a strong central bank mechanism,” he told state media on the sidelines of the two sessions.

This has made the PBOC more dependent on the party, in a nutshell

The proposed changes have not been met with enthusiasm from all quarters. Garcia-Herrero said passage would likely heighten concerns over whether the PBOC should still be defined by the standards of modern central banking.

“The latest changes have entrenched these doubts,” she said, citing its diminished autonomy in policymaking.

“This has made the PBOC more dependent on the party, in a nutshell. That’s a whole new ball game.”